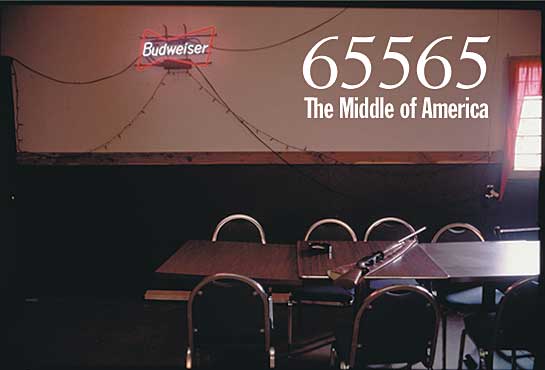

On a perfect Sunday afternoon in Steelville, Missouri, a hundred of its more prominent residents are holed up in the long corrugated metal warehouse of the private country club on Highway 8. A couple are at the bar. The rest crowd tables in the dim cavernous room beyond it, their cans of Stag within easy reach. The only light penetrating deep enough to reach the hard pale faces under camouflage hunting caps comes from a pair of small windows.

A barmaid calls a number, and a man lumbers out of the shadows. He grabs his gun and rests the barrel on the sandbag on a sill. Seconds later the room is jolted by a deafening 12-gauge report. Then he pulls the barrel out of the sunlight, ejects the spent shell, and returns to his seat to find out if his aim was true enough to win the pork chops or ham or beefsteaks in this fund-raiser for the high school baseball team.

In Steelville, a hardscrabble town of 1,429 about 80 miles southwest of St. Louis, there has never been a clear line between recreation and nutrition. With spare rolling hills and vistas just big enough to take them in, this portion of the Ozarks foothills seems to have been created to fit the scale of the human eye, but the land isn't good for growing anything but trees. The homesteaders who arrived in the 1830s counted on deer, turkeys, and squirrels to augment their minuscule harvests of beans, taters, and corn, and with more than half the current households taking in less than $15,000 a year, a lot of Steelvillians still do.

Steelville was once the demographic center of the United States (the 2000 census has moved that spot west to Edgar Springs), but the challenges of this beautiful, unbountiful terrain have given the town a character well outside the mainstream. America's culture is about getting rich. Steelville's is about getting by. It's one of the few places left in the continental United States where living on little more than skill and resourcefulness is not a disgrace but a point of pride.

Earl Halbert, 89, and Eldon Dunlap, 85, are high priests of the old Ozarks lifestyle. Dunlap describes his Depression-era childhood as "a world of trouble," in which his whole family lived on the three dollars he brought in a week, and Halbert recalls how he once quit an aboveground day job for night shift in a bauxite mine because it paid an extra 50 cents a day. Yet both seem more amazed than embittered, and the scripture-quoting Halbert is as upbeat as a TV evangelist.

"Make yourself comfortable," he says at his farm in the holler. "We're just hillbillies here." A red bandanna nattily folded in the back pocket of his overalls, Halbert explains that due to the soil, making money from farming was not in the cards. "You were lucky if you could grow enough to almost feed your family and fatten a few hogs," he says. "But if you knew what you were doing, you could make up the difference in the creeks and woods, and if there was something that absolutely needed buying, you could haul some timber to a mill or cook up some sorghum molasses."

If, like Halbert's legendary late friend Treehouse Brown, you were "tough as a pinewood knot" and so inclined, you could live your whole life quite comfortably outside the official economy. And if you were willing to add a succession of low-paying wage jobs, you could end up like Halbert and Dunlap, sitting pretty in old age on sizable spreads. "It's been a hard life," says Halbert, "but also a pleasant one."

The rough thrill of country life isn't reserved for elders. In the late afternoon I'm welcomed at a birthday party on a scruffy farm at the edge of town, where a couple dozen men and women in their twenties lean against the long bed of a logging truck as if it were a bar. For refreshments there is a cooler of Stag, boxes of charred venison steaks and elk burgers, and a bag of very spicy venison jerky. For entertainment there are horseshoes and the Dixie Chicks coming from the stereo in a flat-bottom fishing boat towed into the yard. Although the sun is dipping fast, there is no talk of moving inside, and in a few hours when it gets really cold, they'll drag the logs off the pickups and build a bonfire. The only other amusements are the lewd novelty items for the birthday boy.

Here I make the acquaintance of a six-foot-three-inch, 220-pound Gen-X logger named Nick Adams, who sports gold Oakleys and a buzz cut and talks about his work with the charisma of a 22-year-old living exactly the life he wants. In high school Adams was a good enough bareback rider to attract rodeo scholarships, but seeing no point in deferring the inevitable, he went to work for his even more Bunyanesque six-foot-six-inch old man, Larry Adams.

In the mornings they pull up to a site in two 60-foot logging trucks. When they've dragged out enough oak or pine to fill them both, they're done for the day. They work year round--the cold of winter offset by the lightness of the trees, whose sap has run back into the ground--and they'll keep cutting until one of them gets killed or the woods are gone. "Logging," says Adams, "isn't something you retire from."

And when Adams isn't cutting, he's still in the woods hunting or fishing. Steelvillians have three beloved ways of plucking fish out of the crystal-clear Huzzah and Courtois (pronounced COAT-a-way) Creeks. There's gigging, a nocturnal winter activity using a flashlight and a spear or gigging pole, and snagging, which involves hanging a heavy hook from a rod, throwing it into the creek, and dragging it back across the bottom, hopefully with a fat ugly paddlefish flapping at the end.

Adams's favorite is the spring rite of grabbing. That's where you dangle a hook from an overhanging limb, and when the fish come schooling by, you yank them right out of the water. Adams spits out a sluice of tobacco juice as his pregnant wife stands beside him. "I live for grabbing suckers," he says.

"Steelville's a southern town laid out like a western town," explains Nancy Cole, gazing at the seven-block Main Street on Highway 19 from L & J Package Liquor to the Hometown Café. Having arrived in Steelville only 21 years ago, Cole, a 53-year-old with cropped gray hair who likes to listen to John Prine, realizes she's a long way from shedding her newcomer status. Nevertheless, her droll hospitality has made Willie Mole's, her gift shop/antiques store/old-fashioned ice-cream parlor, one of Main Street's more productive gossip factories.

Sitting at the counter are Bob Hollenbeck, one-sixth of Steelville's police force, and Anyes Stafford, who works the register at the gift shop next door. Both stop in many times throughout the day to help each other and Cole get through the considerable stretches between sales and crimes. The burly, mustached Hollenbeck, who is reputed to make an excellent pâté, often talks recipes with Cole, and, if she follows through with her plan to put in a little restaurant, may moonlight as her chef.

Stafford came from Paris 35 years ago when Robert Bass, the scion of one of the town's handful of well-off families, brought her back after his military stint in Europe, although she has long since divorced him for a variety of reasons Cole sums up as "bad behavior."

Also visiting is Pam Clary, the town's young and restless veterinarian, who recently married an airline pilot. Before the morning is over, I learn how the lesbian who lived up at the vineyard accidentally shot herself while doing laundry and about the teenage busboy who got busted for manufacturing amphetamines in his kitchen.

In Steelville, town and country exist in opposition. You live in the "country" and you come to "town," and while the country is a male preserve, the proprietors of Main Street are mostly women. Every place I frequent, from the Spare Rib Inn to Meramec Wedding Creations, where a girl getting fitted for a gown tells me about borrowing her cousin's boyfriend for the high school prom, is run by women, and they have proved as adept as Ozarks trailblazers at living off the gristle of the land.

But while the rugged outdoor pleasures of Steelville maintain a strong pull on its men, for women Steelville seems like a posting in a foreign land, something you make the best of. You join the Liquored Up Ladies Literary League or maybe, like Vicki Manzotti, open the Cinnamon Stix Tea Room and offer the first menu in town that isn't slathered with gravy. Or if, like Clary, you're young and marketable enough to have real options, you sell your practice and get the hell out of town.